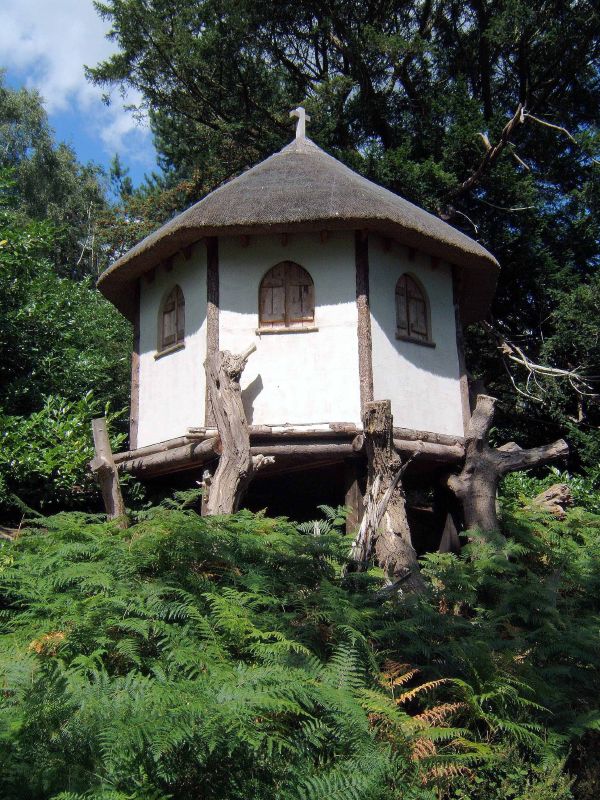

The image you just clicked is a photo of an ornamental hermit hut.

Ornamental hermits were men in the 18th century who were paid to act and live like hermits on enormous European estates. Visitors to the estate could visit them. In the case of "Father Francis," the hermit of the Hawthorne estate, "you pulled a bell, and gained admittance" to his hermitage, where you could sometimes find him sitting barefoot besides "a skull, the emblem of mortality, an hour-glass, a book and a pair of spectacles," the vanitas still life come to life.

The Hermit of Hawthorne

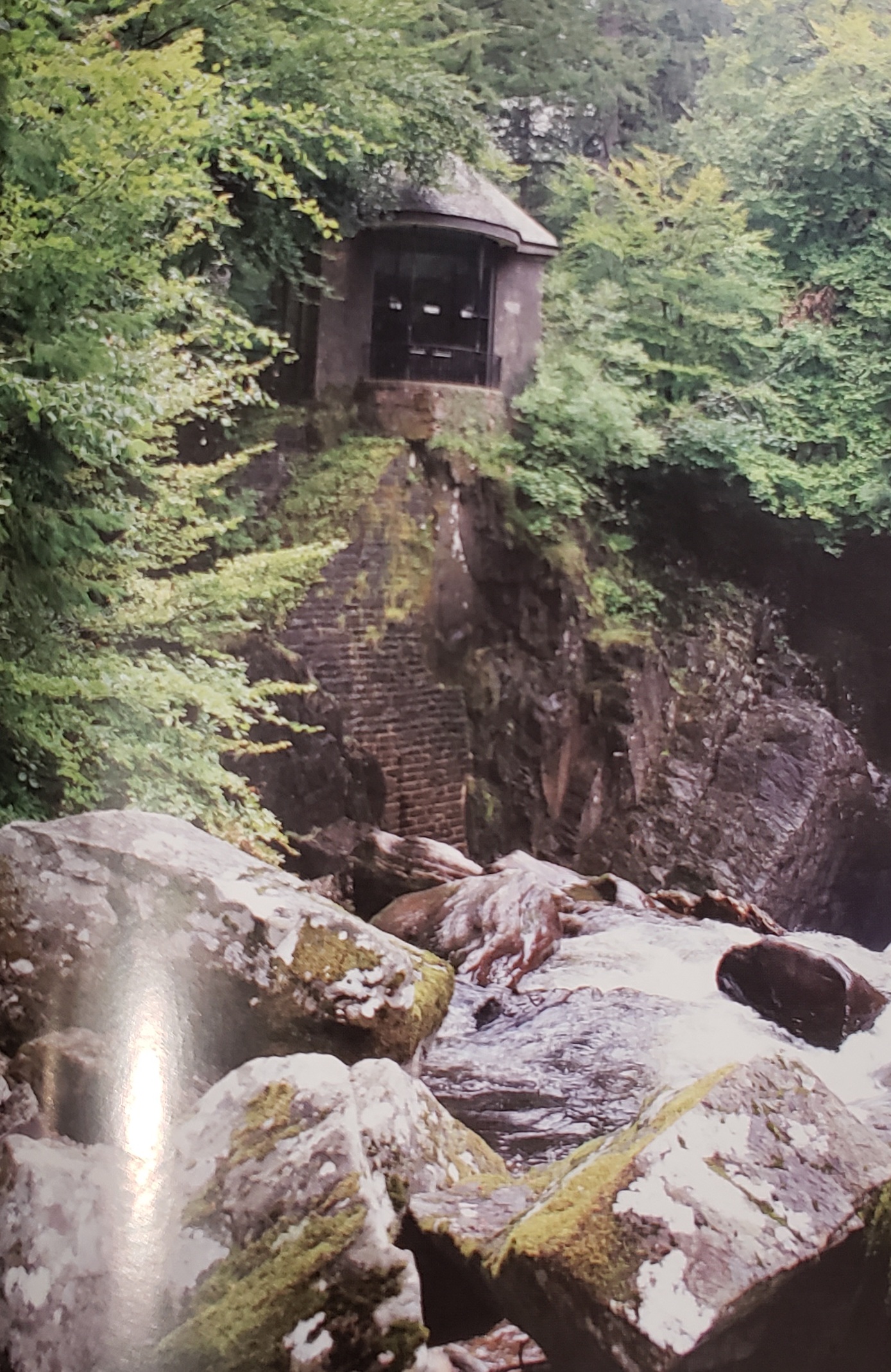

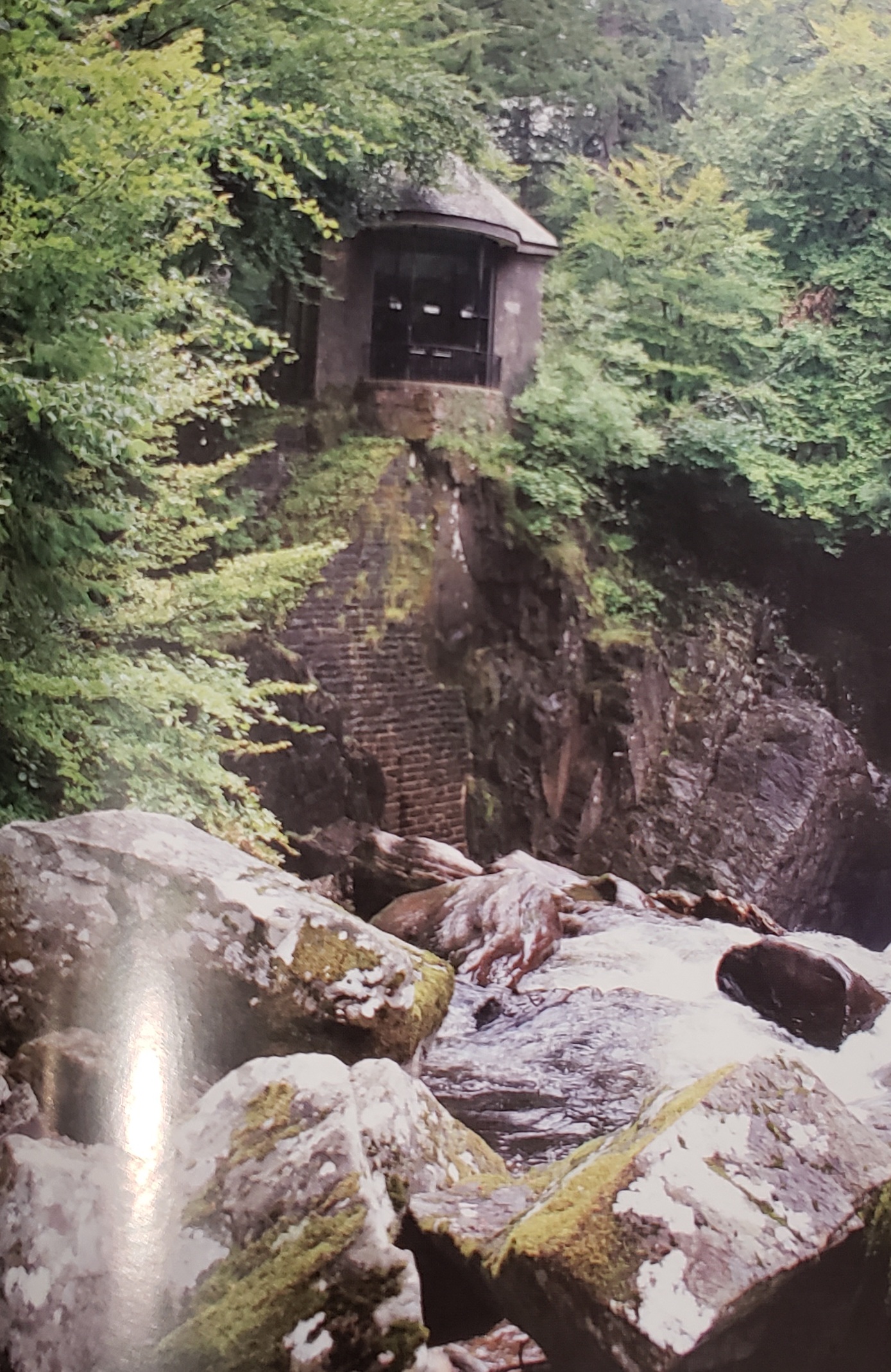

The Hermitage of Tollymore

Certain historical documents suggest that landowners would send out advertisements in the local papers. In a table talk of Romantic poet, Samuel Rogers, there's a comment that reads "Archibald Hamilton, afterwards duke of Hamilton (as his daughter, Lady Dunmore, told me) advertised for 'a hermit' as an ornament to his pleasure grounds; and it was stipulated that the said hermit should have his beard shaved but once a year, and that only partially."

Another reported advertisement reads: "Mr. Powyess, of Marcham...advertised a reward of 50 pounds a year for life, to any man who would undertake to live seven years under ground, without seeing anything human: and to let his toe and finger nails grow, with his hair and beard, during the whole time...Whenever the recluse wanted any convenience, he was to ring a bell, and it was provided for him."

Another report: "Mr. Hamilton advertised for a person who was willing to become the hermit of that retreat, under the following among many other conditions: that he was to dwell in the hermitage for seven years; where he should be provided with a Bible, optical glasses, a mat for his bed, and a hassock for his pillow, and hourglass for his time-piece, water for his beverage from the stream that runs at the back of his cot."

It's uncertain where the ornamental hermit fashion started. One possible link is to the 15th century Italian hermit, St. Francesco di Paola, who enjoyed a sort of "celebrity status" and was well-known to have lived in seclusion on his father's estate. The trend also has roots in actual hermits who lived on the estates of wealthy landowners.

The first documented ornamental hermits were located on Italian and French estates, and the trend later arrived to England in the second quarter of the 18th century.

Father Francis of Hawthorne was sometimes reported to be replaced with a stuffed dummy dressed as a druid with a fake white beard and a long cloak.

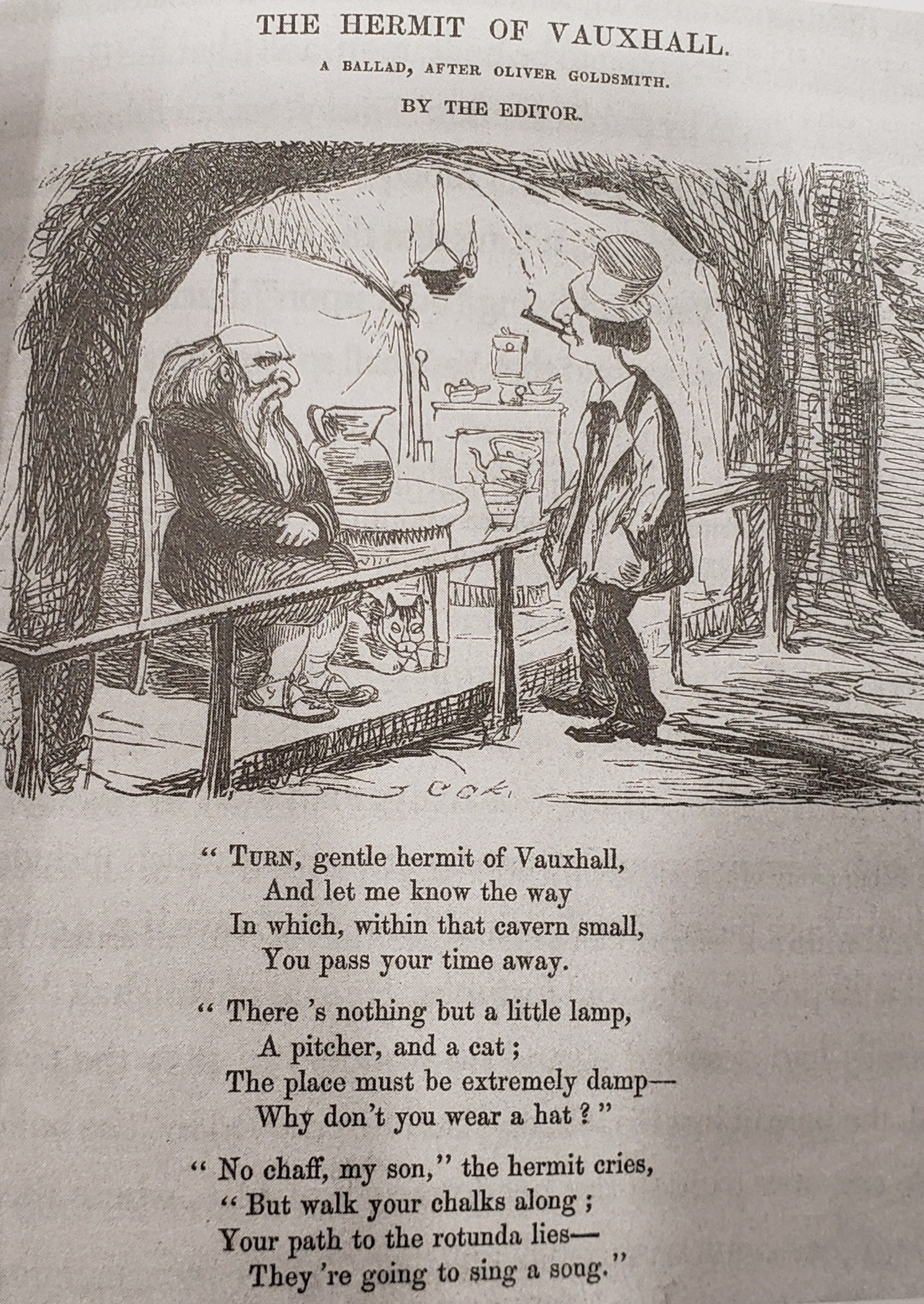

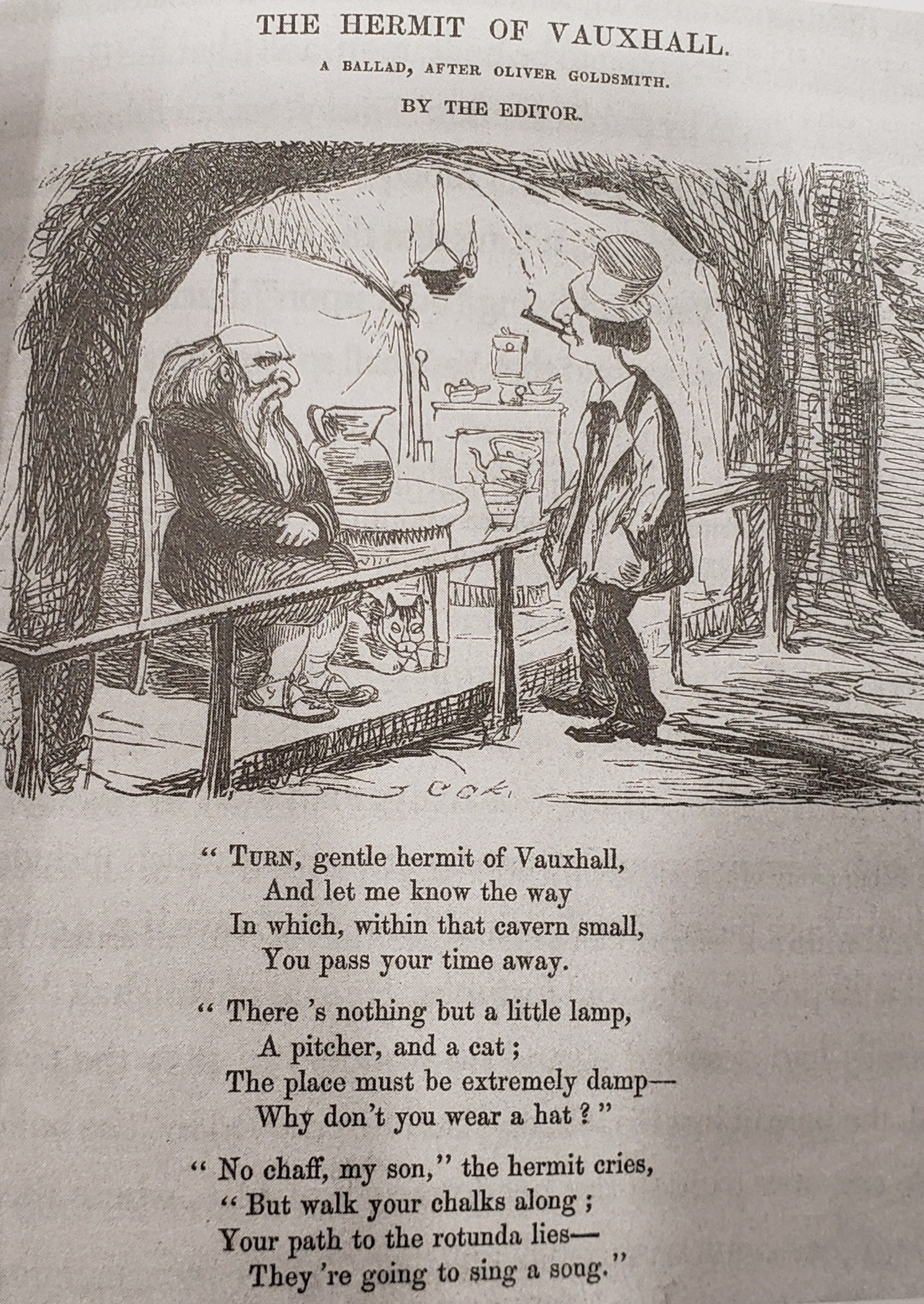

A ballad to the hermit of Vauxhall

The Hermitage of Dunkeld

One of the causes behind the ornamental hermit's popularity in England was the nationalist and antiquarian interest in the character of the ancient British druid. In the 18th century English imagination, a hermit wasn't just some guy who lived in seclusion. He was also a mysterious figure with ties to an older, more fantastical world.

The existence of the ornamental hermit can also be better understood when you consider the horticultural history of European garden estates. In the eighteenth century, there were two general approaches to garden design: natural and associative.

Natural garden design was more in line with the period's romantic ideals of nature, in which the natural world as it "really was" was superior to any artifical or manmade design. The associative garden focused more on the garden as an interactive exhibit that ellicited emotion from the viewer. Associative gardens implimented windmills, artificial grottos, pavilions, escarpments, and of course, hermitages.

By the time the ornamental hermit trend became popular, the role of the hermit as a real job had mostly gone away with the rise of the Anglican church and the dissolution of many English monastaries. In the eighteenth century, the hermit was mostly just a fashionable symbol, which elicited the notion of "contemplative solitude and pleasurable meloncholy."

"Pleasurable meloncholy" is another 18th-19th century notion that was largely tied with the romanticsm trend. It's an idea that's somewhat difficult to frame and define, but can be seen everywhere in the work of many popular artists and writers of that period, such as Milton and Jane Austen.

"Pleasurable meloncholy" = ???

The subject is oftentimes alone in nature. Their soul is full and there's a satisfaction in being alive, but that satisfaction isn't rooted in joy or happiness but something else. The subject's life is oftentimes simple but lonely. There is an intermingling bittersweetness that comes from the vast silence of the landscape.

In England, there were only about six estates that were recorded to house ornamental hermits. These estates were Painshill, Hawkstone, Woodhouse, Tong, Selborne, and the Vauxhall Gardens. There were other estates throughout Europe that contained largely unnocupied ornamental hermitages. These hermitages were sometimes just used as retreats for the landowners, but were sometimes displayed as the homes of "imagined hermits," which could take the form of statues, wax figures, or stuffed dummies.

Many hermitages were covered in moss and shrubs in the attempt to give the buildings the appearance of age.

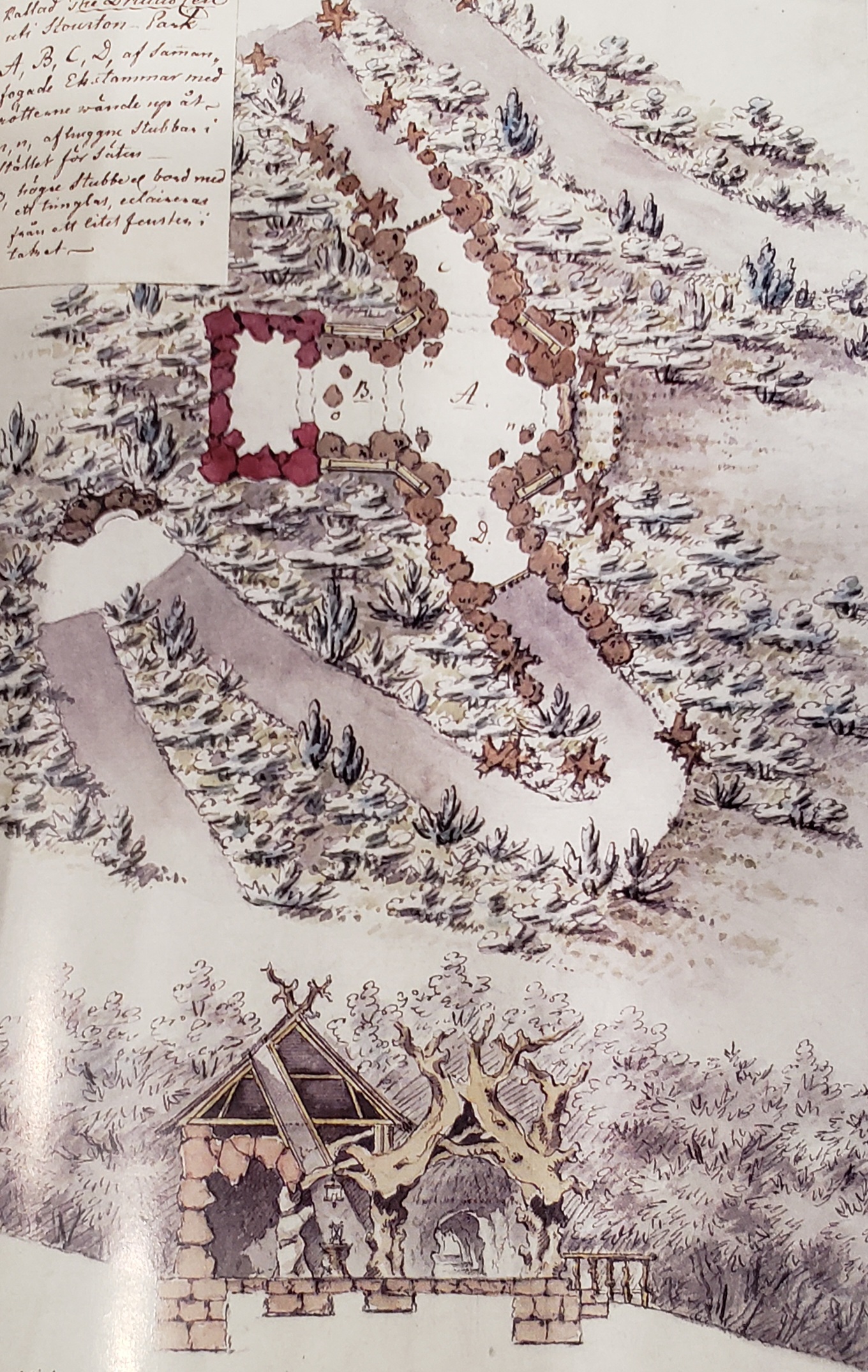

The fashion of the ornamental hermit is rooted in the literary and artistic genre of the pastoral, which ties itself with the architectural designs of the hermit huts. Pastoral artictectural design roots itself in the idea of a simple life in nature. "Such buildings gesture at our wish to be connected with our rural orgins."

As the history of the ornamental hermit makes clear, the history of the European hermit is not just the history of men and women who lived in seclusion, but also a history of fashionable trends and symbols and stories. Maybe this has more to do with the fact that many of the historical documents concerning real hermits and friars and anchorites have been lost in time, but a tremendous percentage of the information I found on eremiticism in Europe has to do with artists, writers, and designers re-creating the idea of the hermit in paintings, poetry, stories, and of course, garden design.

The history of the ornamental hermit is also a history of people with lives of tremendous wealth and comfort suddenly invested in a life of supposed ruggedness, austerity, and isolation. To desire or admire the life of a hermit might oftentimes come from an ignorance for what that life actually entails.

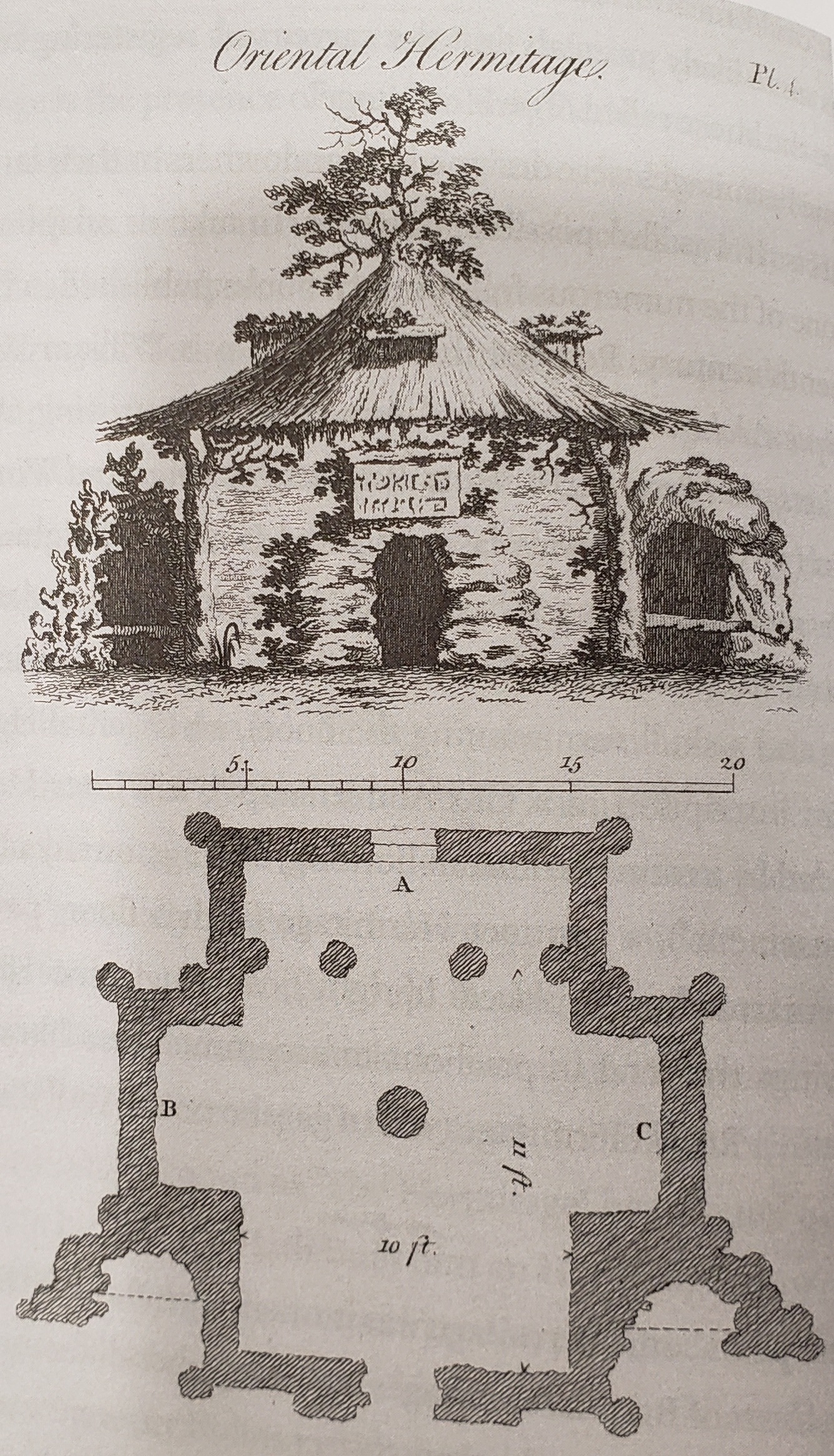

Most ornamental hermit huts were made of wood and thatch. Some were called "root houses," and were literally made to appear like they were created from gnarled roots picked up from the forest floor. The first recorded English root house was constructed in 1747 at Badminton. It was known as the Hermit's Cave.

Jan Sadeler's "Origen building a hermit's cell"

The Hermitage of Oriel Temple

Inscribed in a plaque above the front door of the Hermit's Cave was an inscription in Latin. The translated Latin is as follows: "Here Urganda in woods dark and perplexed, inchantments mutters with her magic voice." The name, Urganda, refers to a magician featured in a Spanish romance titled Amadis de Gaula. Once again, a demonstration of the hermit hut as a fantastical bridge to an imagined ancient history of druidicism and magic.

It can be speculated that a modern-day cultural remnent of the ornamental hermit can be found in the garden gnome. The first garden gnomes were constructed in Germany in the 1840s and wore long white beards and pointed hats. The pointed hat, in fantastical druidic fashion, was sometimes worn by ornamental hermits, such as the Reverend Henry White.

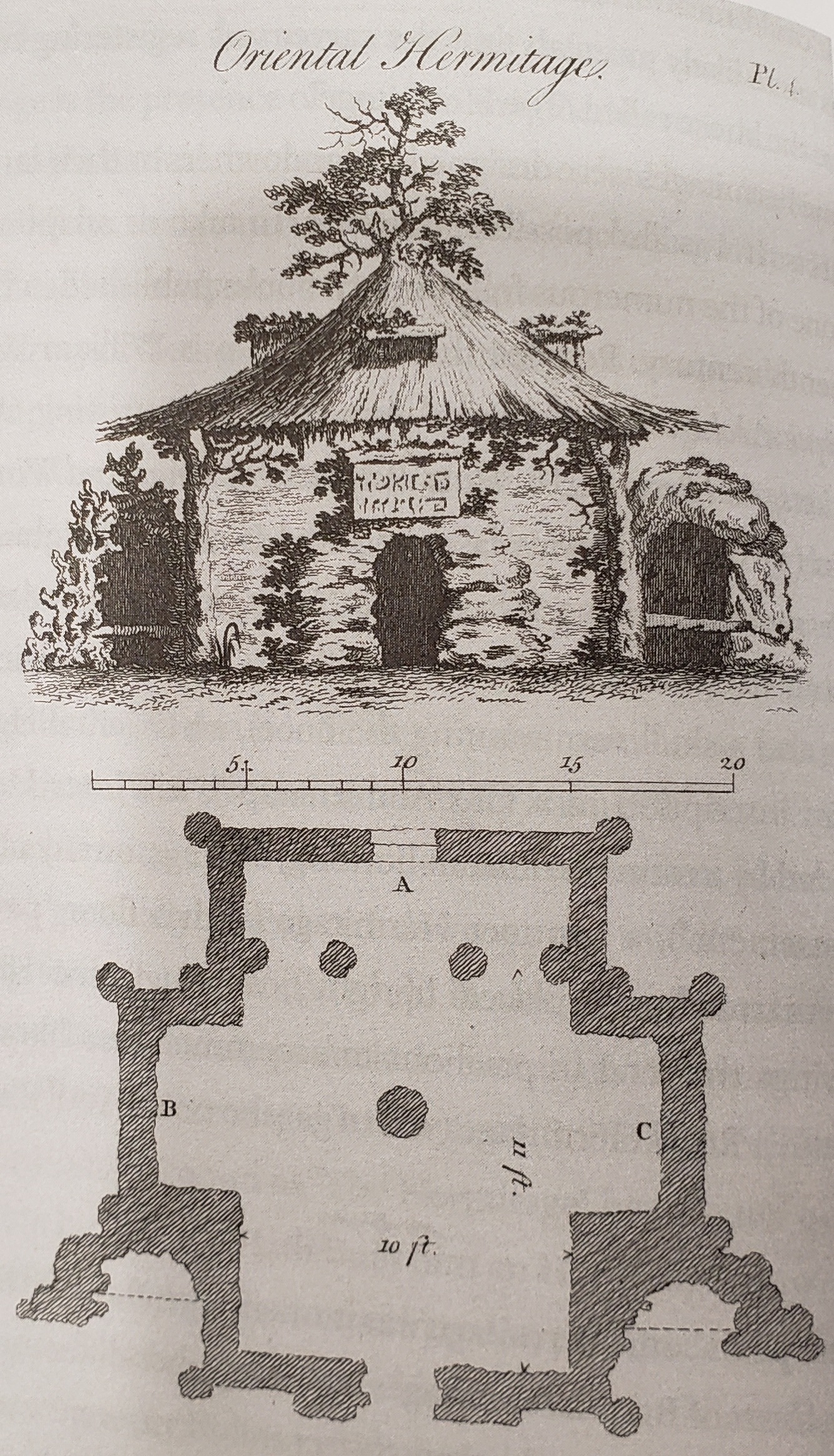

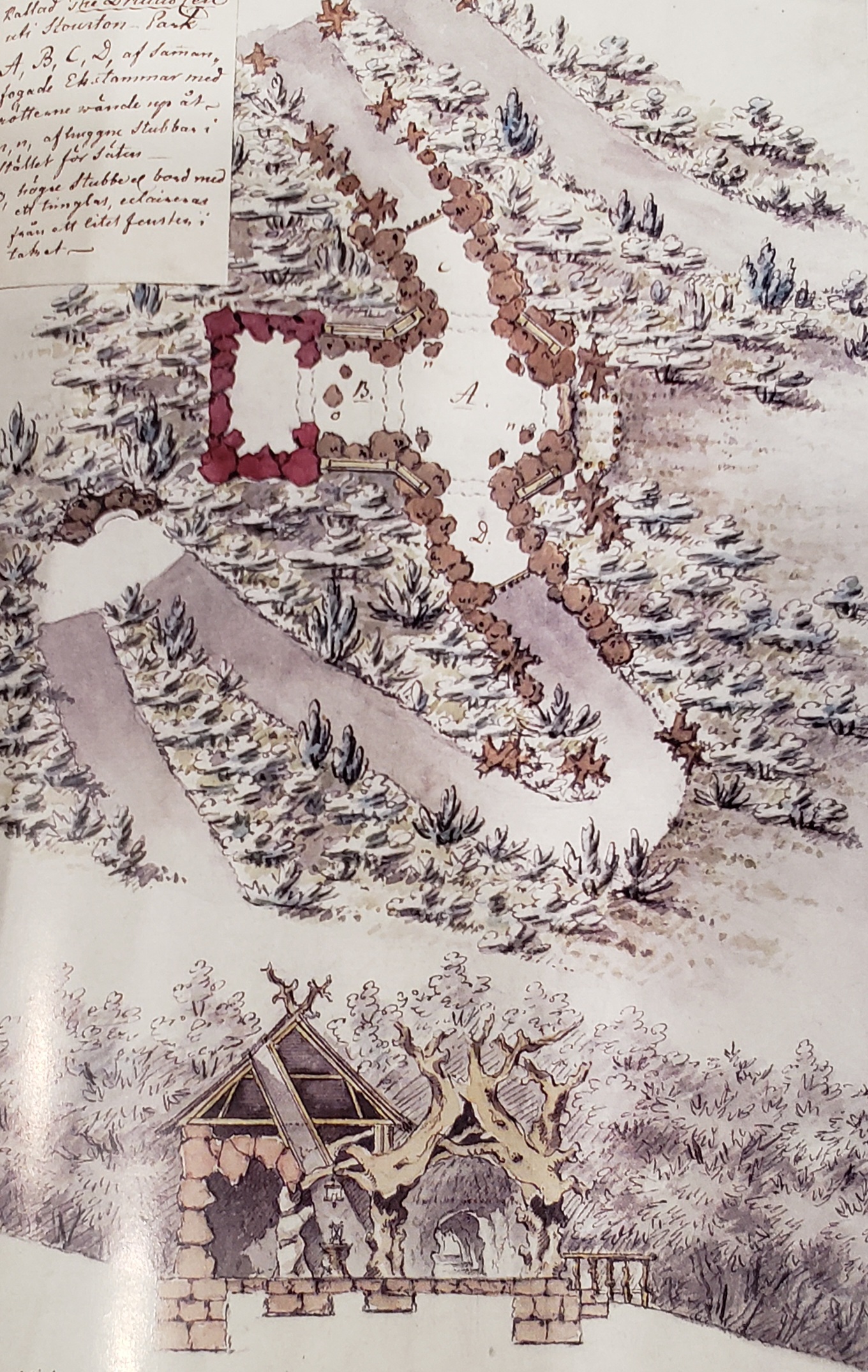

Many of the ornamental hermit huts, constructed mainly of wood, rotted away. A few of the stone huts have survived, but they have been heavily renovated. Some of the design plans and sketches for the huts have been discovered and preserved.

Designer F.M. Piper's drawing of a hermitage at Stourhead estate

William Wrighte's design for a potential hermitage

A "modern day" hermitage was constructed on the Painshill estate in 2004. David Blandy, a performance artist, spent two weeks as the new Painshill hermit. Due to Health and Safety regulations, Blandy was not allowed to stay in the hut overnight. He grew his hair long, didn't wear shoes, dressed as a Buddhist Shaolin monk (?), and didn't speak the entire time

In 2002, the Shugborough estate in Staffordshire constructed a hermitage and created a exhibition similar to Painshill's. Rather than hiring a performance artist, they sent out an advertisement and offered 600 pounds to anyone willing to "perform the role of Resident Hermit."

The project manager of the Shugborough hermit exhibition explained that the mission of the project was "to enquire about the relevance and resonance of the concept of the 'ornamental hermit' in a contemporary context...The project explores and contests the dread and contempt society now displays for the once fashionable ideal of solitude. Whilst, today, the wish for self imporovement is on the rise; by contrast, the wish to be alone is not only unfashionable, but regarded as a sign of failure or unsocialbility."

Wanting to be alone can so confusing! The desire for solitude sits at a weird place between fantasy and reality, the productive and the unproductive, intelligence and stupidity, healthiness and unhealthiness. I want to believe I've felt "pleasurable meloncholy" before, but trends like the ornamental hermit make me doubt the stability and reality of such feelings, and whether or not they're worth my time to pursue. This archive project was made partially because I wanted to pursue what intentional solitude looked like in a real sense, but so much of what I've found has just been design and high-mindedness. It's just people re-creating and enjoying a factsimily of what interests me.